As electric vehicle demand and production grow, uncertainty regarding battery material availability and price weigh heavily on Rivian and other car makers.

January 29, 2023

As the global economy continues churning in early 2023, demand for battery-driven electric vehicles continues to be robust. As part of the Redburn CEO Conference in late November 2022, RJ Scaringe, founder and CEO of Rivian Automotive Inc. said the backlog for the company’s R1T electric pickup truck and R1S electric sports utility vehicle extends well into 2024. Rivian has added a second shift at its Normal, IL, plant and broke ground on a new $5 billion automotive plant in Georgia to ramp up deliveries.

But one of the least-talked-about challenges the company, indeed the entire electric vehicle (EV) industry is facing, is the uncertainty regarding battery materials, as electric vehicles continue moving from single-digit penetration to approaching 100 percent in the foreseeable future.

“Lithium hydroxide pricing today is in the mid-70s (dollars per kilogram),” Scaringe says. “A year ago, it was $10, and the cost to make a kilogram is maybe $6 to $9.50, depending on the source. We see lithium pricing staying high; the same with nickel. At the end of the day, these are limiting factors on how fast the entire market can electrify.”

Play the long game

Certainly, there is an aggressive transition to EVs being undertaken by automakers, but this requires a long-game approach, says automotive editor and analyst Gary S. Vasilash. “Let’s face it: ICE-powered vehicles aren’t going to suddenly go away. So, gasoline of some sort will be required for some time to come. And while e-fuels may be expensive and not particularly efficient to produce, keep in mind that about 10 years ago the price of a kWh from a lithium-ion battery was on the order of $1,200, so that didn’t seem particularly reasonable.”

It's reasonable now. According to the Bloomberg NEF (BNEF) 2020 Battery Price Survey, which considers passenger EVs, e-buses, commercial EVs, and stationary storage, average pack prices will hit $101/kWh this year. At this price point or thereabouts, automakers should be able to produce and sell mass-market EVs at the same price (and margin) as comparable internal combustion vehicles in some markets. This assumes no subsidies like last year’s Inflation Reduction Act reported on earlier in this series are available. Naturally, actual pricing strategies will vary by automaker and geography.

Such kWh price reductions are thanks to increasing order sizes, growth in BEV sales, and the introduction of new pack designs, among others. More efficient manufacturing approaches will continue driving costs down in the near term (see “Boom-Time Battery Production: What OEMs Should Know,” published earlier in this series).

Buy or build?

As a result, Rivian’s Scaringe describes the way he and other vehicle manufacturers allocate capital to source batteries and materials is changing dramatically. Regarding battery manufacturing and obtaining raw materials, “there’s not a single solution addressing the scale we want to operate at. By design, we have a basket of agreements we use with partners and developing our own facilities to achieve dedicated cell capacity and supply control.” This acts as a means of balancing risks with suppliers producing cells, packs, and other components on supplier-owned equipment and OEMs like Rivian building facilities and buying their own equipment.

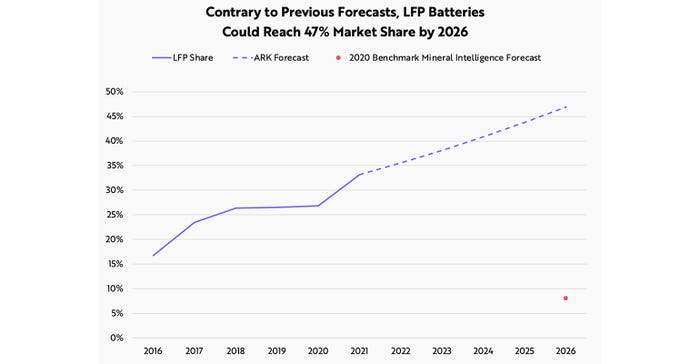

Buy versus build becomes even more important of a balancing act in an environment of changing battery chemistries. “Today our vehicles are high-nickel,” Scaringe says. “We’ll be adding lithium-iron phosphate (LFP) for our commercial vehicles (the company builds and sells electric delivery vans for Amazon and other customers) and plan to use them for consumer vehicles as well.”

High-nickel batteries are well-established with performance metrics and an emerging charging infrastructure, but nickel is expensive, competitively sourced in other industries such as steelmaking, and markets are volatile. Last March, the London Metal Exchange cancelled $4 billion in nickel trades and suspended trading more than a week following a short squeeze by a Chinese steel manufacturer that sent prices soaring by more than 240 percent.

LFP batteries, by comparison, are lower cost due to the wide availability of iron and phosphates in the Earth’s crust. As they contain neither nickel nor cobalt, sourcing concerns, and in some cases human rights-related issues, are greatly reduced.

More to the point, research shows LFP batteries deliver considerably longer cycle life than other lithium-ion chemistries. Most conditions report more than 3,000 cycles, and under optimal conditions LFP batteries can achieve more than 10,000 cycles. NMC (nickel, manganese, cobalt) batteries support about 1,000 to 2,300 cycles, depending on conditions.

With battery design, research, performance, and costs all evolving and rapidly changing, recycling of battery materials stands to redefine sourcing, scarcity, and battery economics. More on this in our next article.

Editor’s Note: This is the 4th in our series on the Brave New World of Battery Manufacturing. The Brave New Battery World. Read Part 1 on the Federal Consortium for Advanced Batteries Roadmap and investment issues; Part 2 on current research; and Part 3 on Boom-Time Battery Production. And watch for further installments covering workforce development, sustainability challenges, and more.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like