Biodegradable device can be used for low-powered electronics—and then harmlessly disposed of.

August 15, 2022

Researchers have developed a new disposable paper battery that they said is well-suited for use with low-power smart devices in the manufacturing and medical sectors.

A team led by Gustav Nystrom, head, applied wood materials at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (Empa), developed the printed device, which is water-activated and can be used for electronics such as as smart labels for tracking objects, environmental sensors, and medical diagnostic devices.

Researchers hope the battery, which contains biodegradable materials, can reduce the environmental impact of single-use electronics that are currently used for these applications and then immediately discarded, they said.

The device is comprised of a cell about one centimeter squared and three inks printed onto a rectangular strip of paper. The strip of paper includes a dispersed layer of sodium-chloride salt as well as a wax coating.

An ink containing graphite flakes acts as the cathode, or positive electrode, which is printed on one of the flat sides of the paper. The other side of the paper includes an ink containing zinc powder, which acts as the negative electrode, or anode.

The battery also includes an ink containing graphite flakes and carbon black on both of its sides atop the other inks to connect the electrodes to two wires, which are located at the wax-dipped end of the paper, Nystrom said.

“We use additive manufacturing processes to print the different electrodes on a piece of paper,” he explained to Battery Technology in an email interview. “All materials are environmentally friendly and the processing is robust and potentially scalable.”

How It Works

The device works using water to cause a reaction that creates energy, researchers said. When a small amount of water is added to the battery, it dissolves the salts to release charged ions. They activate the battery by dispersing through the paper, placing zinc in the ink at the negative end, which releases electrons.

Attaching the battery’s wires to an electrical device closes the circuit so that electrons move from the negative end to the positive end, where they are transferred to oxygen in the surrounding air. These reactions generate an electrical current that can be used to power a sensor, smart label, or other devices.

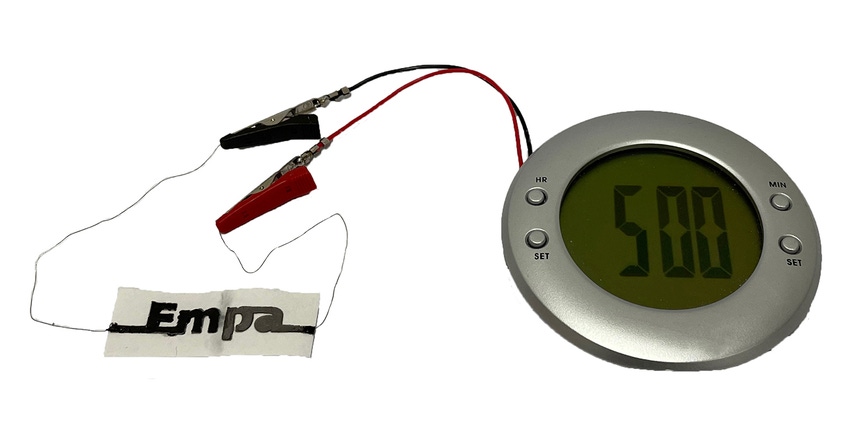

The team demonstrated the battery by combining two cells into one battery and using it to power an alarm clock with a liquid crystal display.

Testing Performance

Researchers also tested a one-cell battery and found that after two drops of water were added to it, the device activated within 20 seconds and reached a stable voltage of 1.2 volts when note connected to another device consuming the energy, researchers said. This performance is in comparison to a standard AA alkaline battery, which is 1.5 volts, they said.

One drawback to the paper battery is that after an hour, its performance decreased significantly because the paper became dry. However, after two more drops of water were added, it maintained a stable operating voltage of 0.5 volts for more than one additional hour, researchers said.

Researchers published a paper on their work in the journal Scientific Reports.

Nystrom told Battery Technology that the best applications for the battery would be when liquid or moisture is already present, such as in the case of biomedical diagnostic kits or environmental sensing systems.

The team plans to continue developing the battery in part to bolster its sustainability by further increasing the amount of zinc used within the ink, researchers said. This also would allow the amount of electricity generated by the device to be controlled more precisely, they said.

Elizabeth Montalbano is a freelance writer who has written about technology and culture for more than 20 years. She has lived and worked as a professional journalist in Phoenix, San Francisco and New York City. In her free time she enjoys surfing, traveling, music, yoga and cooking. She currently resides in a village on the southwest coast of Portugal.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like