A Matter of the Heart: How Lithium Batteries Help Keep Up the Pace

To honor Valentine’s Day, here are some things you probably don’t know about pacemaker batteries.

February 14, 2022

"A merry heart goes all the way- A sad one tires in an hour"

William Shakespeare, The Winter's Tale, Act IV, sc. 3

The modern concept on Valentine’s Day seems to have gotten its start when nature-minded European nobility began sending love notes in February during the bird-mating season. English audiences embraced the idea of a February love holiday and Shakespeare’s Ophelia spoke of herself as Hamlet’s Valentine. The concept of romantic love came into being at about the same period as did the idea that feelings for ones beloved were written in the heart. Valentine’s Day became the holiday for romance and the heart came to symbolize love.

While falling in love has been known to metaphorically jump-start a person’s heart, for those with cardiac disease sometimes romance needs a helping hand. That’s where the pacemaker comes in.

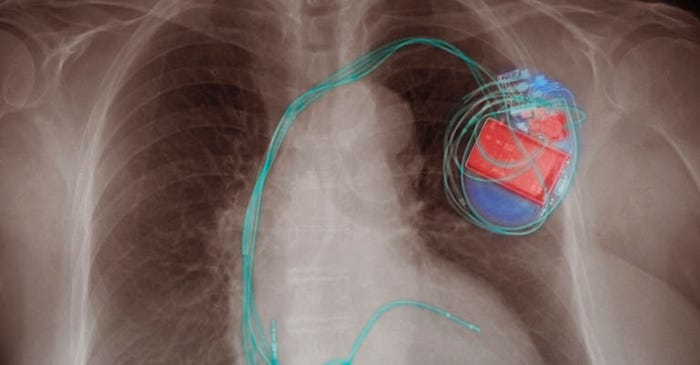

About 3 million people worldwide live each day with an implanted pacemaker, their hearts stimulated with electrical impulses to restore a normal rhythm and allow them to live normal lives. Each year about 600,000 pacemakers are implanted in a process that has become minimally invasive and that usually allows a patient to go home within a day.

It's About the Batteries

Modern pacemakers exist because of batteries. They got their start in 1958 when Rune Elmqvist and Åke Senning in Stockholm, Sweden, developed the first implantable cardiac pacemaker using a rechargeable nickel-cadmium battery. The first unit lasted 3 hours while the net attempt worked for 8 days. The problem was the rechargeable nickel-cadmium batteries.

At about the same time a Buffalo, New York inventor named Wilson Greatbatch began working on an implantable pacemaker using a mercury-zinc battery. Greatbatch’s mercury-zinc battery would last much longer, as long as 2 years, and it became the power source of choice. The mercury-zinc battery was unpredictable in its failures and had a short service life. At one point in the 1960s, the use of radioisotopes was investigated to power pacemakers, but nothing came of it.

In 1968 Wilson Greatbatch acquired the rights to a lithium battery developed by a team of researchers in Baltimore. He began working with the battery, which had no application at the time and by 1975 he had engineered the lithium-iodide battery into a sealed compact package that could be used for an implantable pacemaker. Unlike the unreliable mercury-zinc battery that had a typical 2-year lifespan, Greatbatch’s new lithium cell could last up to 10 years and quickly was adopted as the battery to use in the implantable cardiac devices.

Lithium-iodide battery cells used in cardiac pacemakers have an anode (negative electrode) made from lithium and a cathode that is a combination of iodine and a polymer called poly-2-vinyl pyridine. While neither the iodine nor the polymer is electrically conductive, if they are processed by mixing and heating to approximately 150 °C for 72 hours they react with each other to form an electrically conductive viscous liquid. The molten liquid is poured into the cell eventually cooling to form a solid. When the molten liquid comes into contact with the lithium anode, a monomolecular layer of semiconducting crystalline lithium iodide forms.

During discharging of the cell, the reaction between the lithium anode and iodine cathode forms a barrier layer of lithium iodide. Over time this layer causes the voltage of the cell and this characteristic can be used to estimate the end of life of the pacemaker’s battery cell. Typical lifetimes for a pacemaker’s lithium-iodide battery vary from 3 years for a small child to up to 15 years for a large adult pacemaker that works infrequently.

If you or a loved one has a pacemaker, you can thank battery researcher and inventor Wilson Greatbatch for such an even heartbeat. His work was truly a matter of the heart.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

Kevin Clemens is a Senior Editor with Battery Technology.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like