Tokyo University's Cobalt-Free Battery Breakthrough

Tokyo University's groundbreaking alternative to cobalt in lithium-ion batteries, addressing ethical and environmental concerns.

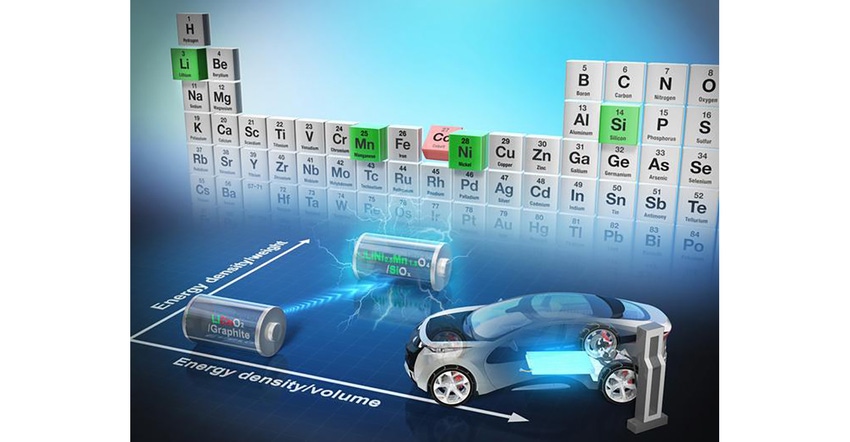

High-capacity and reliable rechargeable batteries are a critical component of many devices and even modes of transport. They play a key role in the shift to a greener world. A wide variety of elements are used in their production, including cobalt, the production of which contributes to some environmental, economic, and social issues. For the first time, a team, including researchers from the University of Tokyo, presents a viable alternative to cobalt, which in some ways can outperform state-of-the-art battery chemistry. It also survives many recharge cycles, and the underlying theory can be applied to other problems.

There is a high chance you are reading this article on a laptop or smartphone, and if not, you probably own at least one of those, and you will find a lithium-ion battery (LIB) inside either device and many others. For decades now, LIBs have been the standard way of powering portable or mobile electronic devices and machines. As the world transitions from fossil fuels, they are seen as an important step for use in electric cars and home batteries for those with solar panels.

Although they are some of the most power-dense portable power sources available, many people wish that LIBs could yield a larger energy density to make them either last longer or power even more demanding machines. Also, they can survive a large number of recharge cycles, but they also degrade with time; it would be better for everyone if batteries could survive more recharge cycles and maintain their capacities for longer. But perhaps the most alarming problem with current LIBs lies in one of the elements used for their construction.

Disadvantages of cobalt in battery production

Cobalt is widely used for a key part of LIBs, the electrodes. All batteries work in a similar way: Two electrodes, one positive and one negative, promote the flow of lithium ions between them in what’s called the electrolyte when connected to an external circuit. Cobalt, however, is a rare element; so rare in fact that there is only one main source of it at present: a series of mines located in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Many issues have been reported over the years about the environmental consequences of these mines, as well as the labor conditions there, including the use of child labor. From a supply perspective also, the source of cobalt is an issue due to political and economic instability in the region.

New cobalt-free battery

“There are many reasons we want to transition away from using cobalt in order to improve lithium-ion batteries,” stated Professor Atsuo Yamada from the Department of Chemical System Engineering. “For us the challenge is a technical one, but its impact could be environmental, economic, social and technological. We are pleased to report a new alternative to cobalt by using a novel combination of elements in the electrodes, including lithium, nickel, manganese, silicon, and oxygen — all far more common and less problematic elements to produce and work with.”

The new electrodes and electrolytes Yamada and his team created are not only devoid of cobalt, but they improve upon current battery chemistry in some ways. The new LIBs’ energy density is about 60% higher, which could equate to longer life, and it can deliver 4.4 Volts, as opposed to about 3.2-3.7 Volts of typical LIBs. But one of the most surprising technological achievements was to improve upon the recharge characteristics. Test batteries with the new chemistry were able to fully charge and discharge over 1,000 cycles (simulating three years of full use and charging) while only losing about 20% of their storage capacity.

“We are delighted with the results so far, but getting here was not without its challenges. It was a struggle trying to suppress various undesirable reactions that were taking place in early versions of our new battery chemistries which could have drastically reduced the longevity of the batteries,” concluded Yamada. “And we still have some way to go, as there are lingering minor reactions to mitigate to improve the safety and longevity even further. At present, we are confident that this research will lead to improved batteries for many applications, but some, where extreme durability and lifespan are required, might not be satisfied just yet.”

Although Yamada and his team were exploring applications in LIBs, the concepts that underlie their recent development can be applied to other electrochemical processes and devices, including other kinds of batteries, water splitting (to produce hydrogen and oxygen), ore smelting, electro-coating, and more.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like