Britishvolt Bankruptcy: What Went Wrong

The UK battery maker’s newly announced insolvency offers stark lessons for other battery startups.

January 24, 2023

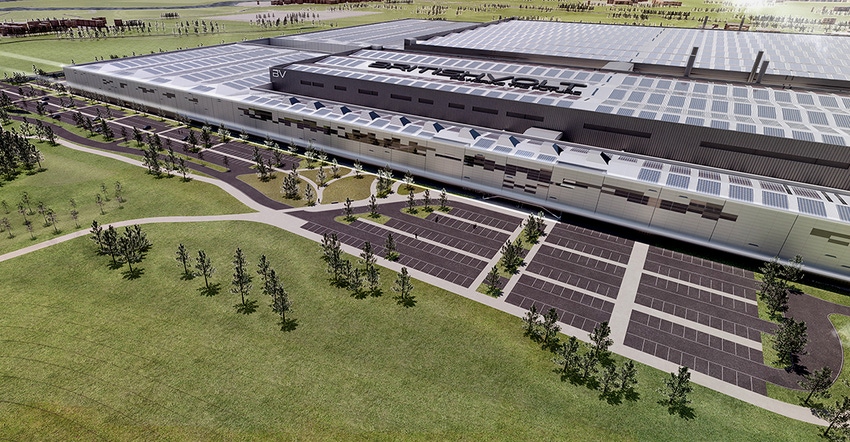

In November 2020, the UK government set aside 2.8 billion pounds ($3.9 billion) to support its mandate of 100% of new cars sold in Britain being electric by 2030. Shorly thereafter, a Britain-based startup, Britishvolt, announced it would build a 38 GWh gigafactory in Northumberland and was awarded a government grant of 100 million pounds in early 2022.

But this was a grant, not a gift. There were conditions, such as attracting private capital, and Britishvolt, after months of attempts to avoid bankruptcy and find new suitors, ran out of money. The company announced it had “entered administration” (became insolvent) on January 17.

Lessons to be learned

After an output of florid media response (“Britishvolt bankruptcy the death knell for UK battery industry,” TechCrunch, Jan. 19, 2023), the reality is less pale horses and more paying attention to basic business.

First, it pays to partner: Britishvolt founders were trying to create a world-class, multi-billion-dollar facility from scratch without the backing of a major manufacturer. “What they did have was a vision which they hoped would surf a wave of political support and attract the necessary funding,” said Theo Leggett, BBC business correspondent in a news story. But construction delays resulted in an eroding of government support, and when Britishvolt asked for an advance on their grant money, the answer was no.

Second, Brexit was no benefit: Bloomberg opinion columnist Matthew Booker wrote on bloomberg.com: “Not all the UK’s industrial ills can be traced to Brexit, but its fingerprints are all over this fiasco. While the company talked up its technology, its inability to draw private investors suggests there was always more hype than reality here. The startup had no major customers. It had agreements with the high-end (and low-volume) sportscar makers Group Lotus Plc and Aston Martin Lagonda Global Holdings Plc, though it’s unclear whether the company ever reached the point of supplying prototypes.

“The immediate question is why such grandiose hopes were invested in an unproven project to begin with. Britishvolt went under without ever producing a commercially viable battery.”

Third, don’t put your hope in hype: What was produced in abundance, Booker relates, was PR. Then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson tweeted that Britishvolt and the newly announced gigafactory confirmed “the UK’s place at the helm of the global green industrial revolution,” an impressive demonstration of faith in a startup with no track record in electric vehicle battery technology.

Simon Moores, CEO of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a London, England-based price-reporting agency and research firm in battery materials, also says of the Britishvolt situation: “Sadly for the UK, the euphoria in political spheres got the better of the on-the-ground reality. Making lithium-ion batteries isn’t easy, especially at scale.”

Not all is gloom for UK battery-making

Although the Britishvolt collapse is a serious blow to the British battery industry, calling it an industry fatality may be premature. For one, the Britishvolt gigafactory site could be an attractive proposition for other battery hopefuls, Benchmark notes. As the former Blyth Power Station coal store, the site has access to Britain’s rail infrastructure and a battleship-worthy deep-water port.

And the UK is not without battery mineral resources of its own, Benchmark continues. Cornwall has lithium resources that several companies are looking to exploit and Green Lithium, a lithium developer, announced Teesside, UK as the location of its upcoming lithium hydroxide refinery. Oil and gas company Phillips 66 produces coke, a precursor to synthetic graphite, in the Humber region of the UK and Vale operates a nickel refinery in Wales.

Furthermore, Britishvolt pitched the possibilities of being able to generate its own electricity from an adjacent company-owned 200-MW solar farm “driving CO2 out of our inhouse processes,” it said on its website.

So while the Britishvolt vision failed to materialize, the educational value remains. As the jazz standard confirms, "Romance without finance is a nuisance."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like