Ensuring the Global Supply of Tungsten Critical to EV Batteries

As China and Russia dominate inventory of the rare metal, Almonty Industries presents an alternative.

January 29, 2024

The critical role of the rare metal tungsten in the manufacturing of batteries for electric vehicles (EV) means ensuring a steady supply is of utmost importance.

In fact, about 2 kg of tungsten goes into every EV in the form of anodes and cathodes, as well as wiring looms in semiconductors—and there are about 2,000 of those looms in every car.

With 90% of all tungsten coming from mines in China and Russia, ensuring the global EV market has access is paramount, asserted Lewis Black, director, president, and CEO of Almonty Industries. Almonty is an international mining company specializing in processing and shipping tungsten—and holds the only portfolio of long-life tungsten mines in the West.

While China prepares to open a huge tungsten mine in Kazakhstan, Almonty is poised to “substantially shift the politics involved with securing tungsten” when The Almonty Korea Tungsten Project’s Sangdon mine comes online within a few months. When it begins production, it will be one of the world’s largest tungsten mines, accounting for 30% of the non-Chinese supply, Black said.

Tungsten: An essential metal in high demand

Tungsten “is the most important metal most people know nothing about, although it is consumed in every facet of the economy,” Black explained. Considered an “alien metal,” tungsten “doesn’t conform to the parameters exhibited by other metals. It has the highest melting point (6,192° F) and the highest tensile strength of any metal in its pure form. It is a mostly non-reactive element: It does not react with water, is immune to attack by most acids and bases, and does not react with oxygen or air at room temperature.”

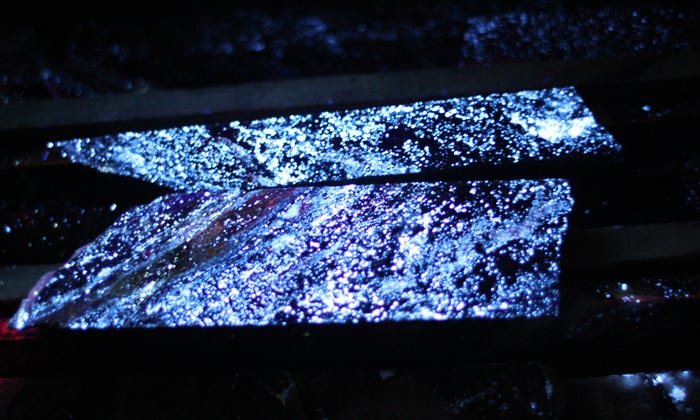

Drill core showcasing high-grade tungsten-rich scheelite ore under UV light. Image courtesy of Almonty

Because of its properties, tungsten is essential for battery technology.

“Its high conductivity allows for much faster rapid charging and an increase in the amount of nickel, which means the battery can hold a charge longer. It is an integral part of an EV, although not as glamorous as lithium. But without the efficiencies that it provides, EVs would be more like a glorified golf cart than a high-performance vehicle.”

About 98,000 tons of tungsten is produced globally at a value of about $30,000 a ton. “It's not a huge industry, but without that 2 kg of tungsten you can't build that EV,” Black asserted.

Hybrid vehicles use the most tungsten, he added, followed by regular gasoline and diesel vehicles, then EVs. “But as EV technologies keep expanding, the EV is now rapidly approaching the same level of tungsten consumption as a regular vehicle.”

The key to future demand rests on the momentum of the EV industry, he continued. With demand softening recently, “the major automakers seem to be pulling back from EVs and hybrids seem like a bigger bet over the short term at least. And tungsten is even more vital for hybrids because of its importance in the gearing system. Tungsten is crucial here because its extraordinary strength and heat resistance can stand up to the vehicle’s constant changing between its electric and gasoline or diesel-powered modes.”

Mining obstacles and opportunities

Regardless of market shifts in EV demand, tungsten has other vital uses—including in military hardware and defensive weapons, semiconductors and microchips—that make access to the metal critical. But mining challenges abound.

“The first problem with tungsten is getting access to it,” Black explained. “It is also extremely difficult to mine as it exists mostly in compounds with other elements. Despite its hardness, tungsten is extremely brittle, and mining it efficiently is truly an art form. A great deal of technical knowledge is required to extract it efficiently, and we are extremely fortunate that one of our tungsten mines in Portugal has been in operation for more than 125 years, giving us a knowledge base on tungsten processing that is five generations deep.”

The Panasqueira mine is joined in Almonty’s portfolio by the Los Santos and Valtreixal facilities in Spain and the Sangdong Mine in South Korea, “which represents 30% of all tungsten outside of China and 7% to 10% of the entire global supply.”

Given Almonty’s unique position as the sole Western owner of tungsten mines, “our plan is relatively simple,” Black asserted: “We are the holdout and plan to be the last man standing in tungsten outside of China and Russia. We have a little corner of the market where we are entirely transparent and vertical, allowing you to trace every movement of that product through our chain as it moves downstream to our clients. Going forward, we will continue to develop our downstream strategy.”

Unique business model

With a track record of operations going back more than 100 years, Almonty has plenty of experience acquiring, processing and selling tungsten—and very little competition.

“We produce the highest grade, cleanest material in the world,” Black said. “We've developed numerous technologies in order to remain competitive, including cutting-edge Mine Safety DX technology that we worked on with Korea Telecom at the Sangdong Mine.”

Almonty CEO Lewis Black. Image courtesy of Almonty.

Almonty sells all its material directly to its clients. “And because we only operate in democracies, we don't have to partner with government entities. Historically, around 90% of our production has gone to US industries.”

Remaining independent “has also allowed us a great deal of flexibility in our approach. For example, I do not have to get approval from some fund that owns 20% or 30% of the company before I can say, introduce a partial sulfur flotation circuit into my gravity plant.”

Adapting to the tungsten market as it has evolved over the past 20 years has been vital to Almonty’s success.

“We've done a magnificent job of developing our mines and they are profitable. Twenty years ago it was really cheap to produce tungsten in China, so we developed technologies that would make us more competitive. But Chinese costs have gone up dramatically since then, while we have focused and invested heavily in our technologies.”

Limited competition—outside of China

Outside of China, competition in the tungsten business is limited, to say the least.

“There are other operating projects out there, but they lose money and they normally close after a short time. We've seen a lot of people come and go because there are a lot of factors to consider when opening up a tungsten mine.

“It would be nice to have a Pepsi/Coke kind of rivalry because then you have something to strive for as you are always trying to beat the next guy and it drives you forward. I don't see that we have that. Therefore, China has always been our Pepsi in that we've always got to make sure that we can compete against China even though they're much bigger and richer than us. In order to survive, we must be able to compete with China even though their companies get state subsidies and other support.”

That said, Black conceded: “We have a great deal of respect for our Chinese colleagues in tungsten. They're extremely good mine operators—but we like to feel that we've held our own against China.”

Taking the long view is key to running a succesful mining business, he concluded.

“In the West, we tend not to look further out than three months, assessing things a financial quarter at a time—and opening a mine is a long, precarious and often miserable journey. Nothing in mining happens overnight, and there are many factors to consider.”

Furthermore, the relationship between supplier and producer “is somewhat tense because the price of tungsten has been very efficiently managed by China for many years as they used state subsidies to keep it in a narrow band. One of the primary reasons for this was because it discouraged new capital from coming into mines outside of China.

“That has kept margins razor thin and you have got to be really good to survive and make money. If you're not, you go to the dogs.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like