Protective Layer Paves Way for Cold-Charging Batteries

Researchers at Penn State have developed a self-assembling solution to protect lithium-metal batteries.

October 19, 2020

Anyone who has driven a car in cold weather knows the annoyance of a battery needing to be jump-started because of the cold temperature. Now researchers at Penn State University believe they may have a solution for this problem by developing a new battery with an extra material layer that can allow for cold charging.

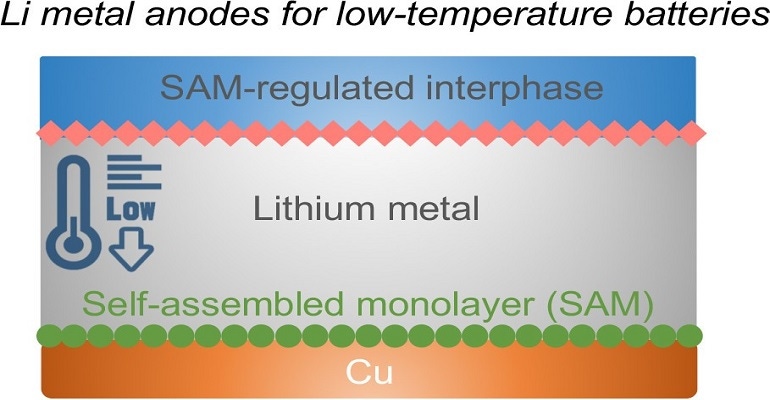

A team in the university’s Battery and Energy Storage Technology Center created the self-assembling layer, which is comprised of electrochemically active molecules that decompose into the components needed to protect the surface of a lithium-metal battery anode, said Donghai Wang, a professor of mechanical and chemical engineering at Penn State who led the research.

"The lithium-metal battery is the next generation of battery after the lithium-ion battery," he explained in a press statement. "It uses a lithium anode and has higher energy density, but has problems with dendritic growth, low efficiency, and low cycle life."

The battery the team designed uses a lithium anode, a lithium metal oxide cathode, and an electrolyte which also has lithium-ion conducting materials, as well as the protective, thin-film layer.

Surface Reaction

The battery alone, without the layer, would tend to grow lithium crystal spikes called dendrites if charged rapidly or under cold conditions. Dendrites—which have caused explosions in lithium-ion batteries--would eventually short out the lithium-metal battery, which decreases its lifetime and ultimate usefulness.

The key to why the layer works is that it performs its function on the surface, tuning the molecular chemistry there, Wang said.

"The monolayer will provide a good solid electrolyte interface when charging, and protect the lithium anode,” he said in a press statement.

To develop the battery, the team deposited the monolayer on a thin copper layer. Lithium hits the monolayer upon battery charging, then decomposes to form a stable interfacial layer.

On-Demand Protection

That decomposed portion of the original layer reforms on top of the lithium that also hits the copper layer as well as the remaining layer. This is what protects the lithium and prevents dendrites from forming.

Researchers reported their work on a paper in the journal Nature Energy. In their results, they said that the key to the technology is that it can form the protective layer when needed, covering both the copper and also the lithium to allow for cold charging.

Wang and the team envision the battery they developed could be used not only for cars but also for drones or batteries used in other applications—such as those underwater—that occur at low temperatures.

However, while the team found that their invention improves the battery by increasing its storage capacity as well as the number of times it can be charged, more work needs to be done to create a commercially viable battery. This is because at this point the device can only be charged a few hundred times.

Elizabeth Montalbano is a freelance writer who has written about technology and culture for more than 20 years. She has lived and worked as a professional journalist in Phoenix, San Francisco, and New York City. In her free time, she enjoys surfing, traveling, music, yoga, and cooking. She currently resides in a village on the southwest coast of Portugal.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like