Chrysler’s EPIC Original Battery-Electric Minivan

Chrysler sold battery-electric minivans in the ‘90s, but lost money on every one.

Stellantis brand Chrysler is promising a battery-electric minivan by 2028, but the company has actually already delivered electric minivans.

In response to California’s zero-emission vehicle mandate, which was set to take effect in 1998, Chrysler tasked an advanced technology group with developing a plug-in vehicle that it could sell to meet the requirement. The minivan was a natural platform for EV technology at that time because of the large size and heavy weight of the battery packs, explained Jim Cerano, program manager of the advanced technology group. “We got questioned about our choice of a minivan, but it was easy to package the battery tray, it carried a lot of weight, it’s versatile, and it was a hot seller,” he said.

The company started with the TEVan, an experimental version of Chrysler’s first-generation van that it sold mainly to electric power utilities. Chrysler sold 66 TEVans, but they were costly, slow, and slow to charge. Not only were the DC motors gutless, but the nickel-iron batteries required constant replenishing of their water levels. “They were clumsy vehicles, but they were out there in 1985,” observed Cerano.

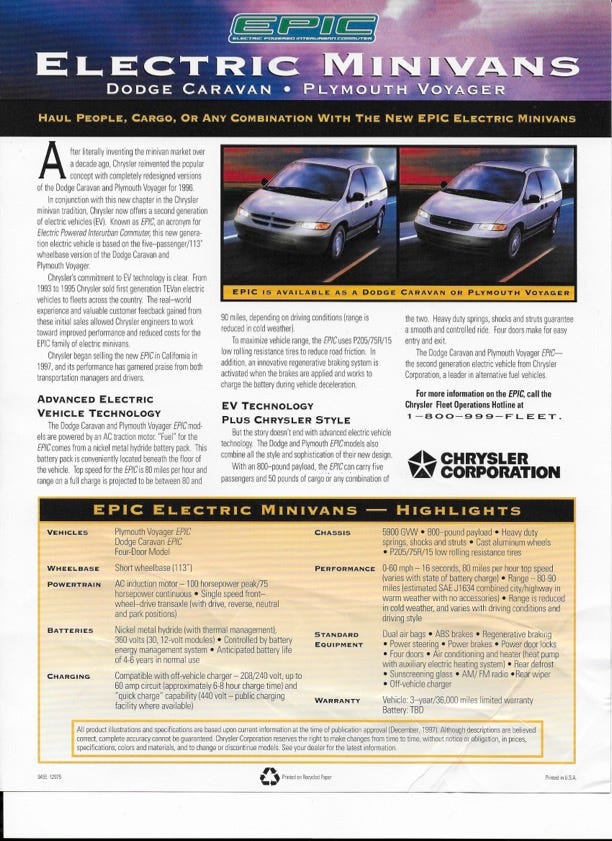

EPIC was Chrysler’s follow-up to the TEVan. The name stood for “Electric Powered Interurban Commuter.” Electrification was designed into the second-generation minivan’s platform so that it wouldn’t be as difficult or expensive to build battery-electric versions, according to Cerano. Chrysler teased the market with a sleek concept EPIC that surely turned heads, but the production EPIC wore the same bodywork as gas-powered vans.

The first EPIC vans employed lead-acid batteries, which did not require continuous topping off of the water level, but they only provided 50 miles of range. Chrysler turned to French battery maker Saft for nickel-metal hydride cells. Each of the 30 modules stored a kilowatt-hour of energy, which gave the EPIC a driving range of between 80 and 90 miles.

Unlike the Panasonic batteries used by other automakers also trying to meet the California mandate at the time, the Saft batteries were liquid-cooled, so the van was able to manage battery temperature as needed to protect the cells, Cerano said.

The van employed an off-board 440-volt DC fast charger that could recharge the pack in just half an hour, which was crucial both for the purposes of testing by Chrysler engineers and by fleet customers who needed to keep the vans rolling throughout the day. “You have to accumulate so many miles in vehicle development so we got it down to half an hour so we could run the cars 24/7,” he explained.

EPIC’s AC induction motor provided 100 peak horsepower (75 hp continuous), which could accelerate the van to 60 mph in 16 seconds and to a top speed of 80 mph. This made the EPIC a technology leader at the time, but this tech came at a price: $128,000 for the EPIC’s bill of materials. That, for a vehicle that sold for $45,000.

Chrysler offered to lease EPICs to fleet customers for $500 a month, and that didn’t help spark demand, recalled Cerano.

The technology was clearly not ready for use by regular drivers and building a lot of them would have bankrupted the carmakers, so California pivoted to permit hybrids to fulfill the requirement along with allowing carmakers to purchase credits from EV specialist companies like Tesla when they emerged later.

Nevertheless, Cerano is proud of the work of his team and that of the teams at rival carmakers who got the most they could out of the available technology of the day. “The seed was planted back then, he said. “The engineers at all three [domestic] companies delivered viable cars that could be mass produced.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like