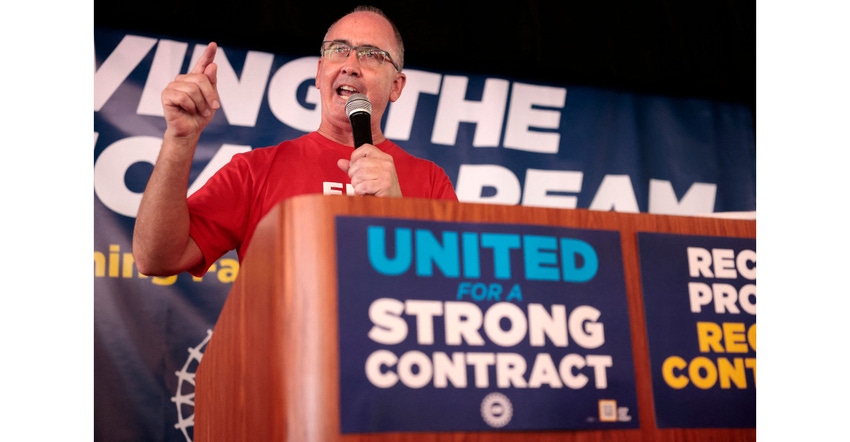

UAW Strike: EV Shift Supercharged Rift Between Automakers & Union

The transition to electric vehicles looms large in contract disagreements between the striking United Auto Workers union and the Big Three US automakers.

September 15, 2023

The current United Auto Workers (UAW) strike against US automakers threatens to bring the American auto industry to its knees and hinder its progress in the shift toward electric vehicles (EVs).

When an 11:59 p.m. deadline passed September 14 without a contract, the union ordered a targeted strike in which UAW workers at a Ford plant in Michigan, a GM factory in Missouri, and a Stellantis facility in Ohio walked off the job. The union is also threatening to scale up the strike, culminating in a potential national work stoppage, in order to maximize its leverage against the Big Three US automakers.

The rift between the UAW and car manufacturers centers on disagreements over contract points including the size of worker raises, the expansion of pension benefits, cost-of-living pay increases, and the ability for the UAW to strike over proposed plant closures. But looming large in the background is also the accelerating transition from internal combustion (ICE) vehicles to EVs.

Shift to EVs poses challenges for US automakers & autoworkers

“The transition to EVs is a key factor in the positions of the union and of the companies,” Erik Gordon, a clinical assistant professor focused on technology commercialization at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business, told Battery Technology. “The companies need flexibility and capital to transition to EVs, and the union wants its members to keep their jobs through and after the transition.”

Although both sides say they support the shift to cleaner cars, it has undoubtedly weighed on the negotiations. For the automakers’ part, the shift from ICE vehicles to EVs has proved costly, potentially impacting their appetite for meeting the UAW’s demands.

“The enormous cost to transition to EVs makes it difficult for car companies to agree to expensive demands like 32-hour work weeks, defined benefit plans, and an end to tiered wages, on top of large wage increases,” Gordon said.

But Arthur C. Wheaton, director of labor studies for the School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University, downplayed the cost to ramp up EV manufacturing as an excuse for automakers’ refusal to cow to union demands.

“It is one factor but not the only factor,” Wheaton said. “Legacy wages and benefits are a bigger reason for the conflict. Automakers were happy to reduce wages and benefits in tough times, and the UAW wants some of them back in good times/high profits.”

From autoworkers’ point of view, EVs, which Wheaton said require around 30% fewer parts than ICE vehicles, represent a potential threat to jobs.

“Assembly plant workers have good reason to be anxious because assembling EVs requires fewer workers, and some skills that were important in assembling ICE vehicles won't be needed to assemble EVs,” Gordon explained.

Disagreement over how to use government support for EV shift

While federal legislation such as the Inflation Reduction Act has led to a boom in jobs producing batteries for EVs, many of those jobs are in nonunionized plants and offer lower wages than those commanded by UAW members.

“The UAW believes federal subsidies should require some labor or community benefits involved instead of boosting profits,” Wheaton said. “Automakers see it as low-wage work (around $16 per hour this year), while UAW wants billions in loans and benefits to be for higher-paid jobs.”

From another perspective, using money from government incentives, loans, and grants intended to support the shift to EVs in the US to instead boost the pay of workers could ultimately undermine the intention of the laws that brought about that money in the first place.

“Some would argue that the government support will be made worthless if the large pay and benefit hikes end up making US production of EVs non-competitive with EVs made in other countries,” Gordon said.

Strike could hurt unionized automakers, bolster nonunion competition

No one knows how long the strike might drag on or what it might take to bring the two sides to an agreement, although Wheaton posits that a resolution could involve government intervention in the form of demanding a prevailing wage or union jobs for battery workers.

“It will be a difficult struggle, but I don’t expect it to be resolved this year,” he said.

In the meantime, the strike could deal a painful blow to the US auto industry.

“It could slow production of the Detroit Three, and it could lead to more manufacturing in Mexico if the strike is extended,” Wheaton said.

The strike could also give an edge to non-union competitors of Ford, GM, and Stellantis, including Toyota, Nissan, Honda, and Tesla.

“The transition to EVs is going to happen no matter what,” Gordon said. “The question is who is going to win market share.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like