New Study Names Nevada Lithium Mine World’s Largest

Earth’s largest previously known lithium deposit comes in at 10.2 metric tons: Thacker Pass could have 120 and support a million EVs per year by itself.

September 19, 2023

Behind its dull research paper title: “Hydrothermal enrichment of lithium in intracaldera illite-bearing claystones”, (ScienceAdvances, The American Association for the Advancement of Science-AAAS, Aug. 30, 2023), lies exciting news. In the midst of a global lithium rush driven by world electrification in service of a cleaner planet, Thacker Pass, a lithium mine located near the Nevada-Oregon border and under exploration since the 1970s, is now estimated to be 10 times bigger than what up to now was considered the world’s largest lithium site—and could handle projected lithium demand for the entire United States on its own.

For those not knowing their illites from their smectites, some background. All current global lithium production is currently sourced from either hard-rock veins or high-elevation evaporitic brines. The AAAS geology study identifies a major third source—volcanoes.

According to a 2022 feasibility study for the Thacker Pass project, owned by Vancouver-based Lithium Americas Corp. (LAC), the Humboldt County, NV, site is located within an extinct 40×30-km supervolcano known as the McDermitt Caldera. It formed approximately 16.3 million years ago as part of a hotspot underneath the Yellowstone Plateau.

After the initial eruption, the McDermitt Caldera collapsed and a large lake formed in the caldera basin. This lake water was extremely enriched in lithium, resulting in the accumulation of lithium-rich clays. Later seismic activity uplifted the caldera, as well as a portion of the surrounding Montana mountains, draining the lake and bringing the lithium-rich moat sediments to the surface, resulting in the current near-surface lithium deposits.

Smectite and Illite

Smectite is lithium-bearing clay occurring at relatively shallow depths and can contain roughly 2,000 to 4,000 parts per million (ppm) of lithium, well worth the extraction. Higher lithium contents, currently rated at 4,000 ppm or greater, are typical for illite clays occurring at moderate to deeper depths.

Thacker Pass clays turn out to be hybrids—illites made from smectites. In the words of the LAC-funded AAAS study, “the unique lithium enrichment of the illite at Thacker Pass resulted from secondary lithium- and fluorine-bearing hydrothermal alteration of primary neoformed smectite-bearing sediments, a phenomenon not previously identified.” This unique geologic enrichment turns out to be a lithium jackpot—whole-rock assays of Thacker Pass illite are coming in at 9,000 ppm lithium, according to LAC.

And there’s a lot of it. The study goes on to cite recent estimates of in-situ tonnage of ~20 to 40 metric tons (MT) of lithium and a possible maximum of 120 MT of lithium to be contained within sediments of the whole McDermitt caldera (the Thacker Pass site occupies a small portion of the caldera’s south end). Even if this estimate is high due to variations in sediment thickness and/or lithium grade, “the Li inventory contained in McDermitt Caldera sediments would still be on par with, if not considerably larger than, the 10.2 MT of Li inventory estimated to be contained in brines beneath the Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia, previously considered the largest Li deposit on Earth.”

GM is in

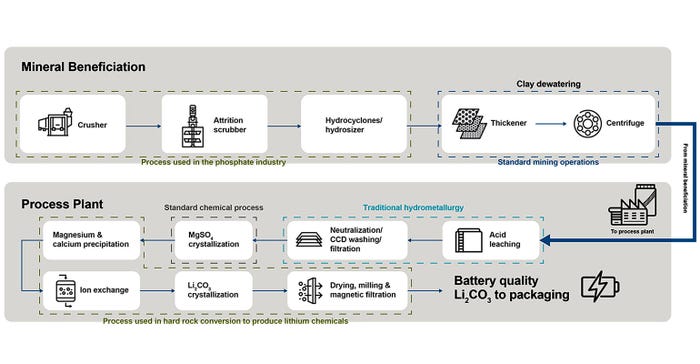

Construction of the Thacker Pass mining and processing complex is underway and initial production is forecast for second-half 2026. The Thacker Pass operation will include a co-located sulfuric acid plant that will convert molten sulfur into sulfuric acid, used for leaching the lithium from the clays. “This process produces steam, which we will use to generate carbon-free power for the processing facilities,” LAC says in a statement. “Co-locating a sulfuric acid plant reduces the number of trucks on the road, as each ton of sulfur can create three tons of sulfuric acid, and sulfur is much safer to transport.”

This past February, LAC announced the closing of a $320 million initial tranche of a total announced investment of $650 million in Lithium Americas Corp. by General Motors, making GM LAC’s largest shareholder and offtake partner. Lithium carbonate from Thacker Pass will be used in GM’s proprietary Ultium battery cells and it’s estimated that the lithium extracted and processed from Phase 1 of Thacker Pass can support production of up to 1 million EVs per year, LAC says.

DOE is in, too

LAC projects the capital costs for the Thacker Pass project at $3.9 billion over seven years. This past February, Lithium Americas received a Letter of Substantial Completion from the US Department of Energy (DOE)’s Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing loan program, moving its application process to confirmatory due diligence and term-sheet negotiations. The next milestone is a Conditional Commitment from DOE. The loan is expected to cover up to 75% of capital costs for Phase 1 construction, LAC says.

And the economic modeling looks as positive as the geology. LAC’s 2022 feasibility study for Thacker Pass forecasts the life of the mine at 40 years, pulling a production total of 2.7 million metric tons of sellable lithium carbonate over that period. While costs and lithium carbonate prices can and do fluctuate, the study lists annual production costs per ton of lithium carbonate over the mine’s first 25 years at $6,743 per year; and $7,198 per year over 40 years. The projected average annual price per metric ton of lithium carbonate over the next 40 years? $24,000.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like